This means that most days, though not all, we get the most out of the precious instructional minutes give to us 45 minutes to be exact. We don’t have a lot of transitions or downtime as students manipulate the learning environment as needed, most of the time, not waiting for me to tell them to get ready for something, find supplies, or any other small things that can end up taking a lot of time.

Instruction/exploration time starts the moment the bell rings and ends when the bell rings again.

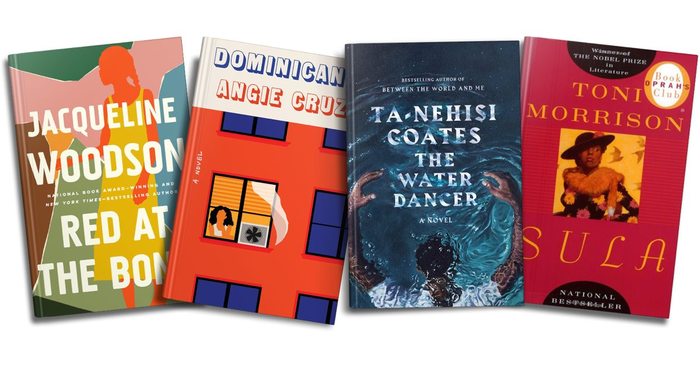

Booked kwame alexander spine of book how to#

At the beginning of the year, we discuss how to be more effective with our time and students quickly set up routines for this to happen. This doesn’t mean we rush, it just means that time is precious in our classroom. I used to take a more leisurely pace when I had the luxury of more time, but now a sense of urgency often drives us forward. We don’t have quizzes or tests either, and so the bulk of what we do takes a week or longer, therefore allowing the students that need extra help or practice to get it in class. It is, therefore, rare that we have an assignment that requires being turned in the very next day. Rather than doing many small projects, I have the luxury in English of focusing on several large projects, we call this being a part of the slow learning movement. This approach has motivated many students to use their class time better, and it has definitely clued me into which kids are working super hard and still having a hard time understanding the work, then leading to further teaching. If they decide to not work hard, then the natural consequence is that they still have work to finish once the class is over. I make sure my students have enough work time in class to practice what they are learning. One of the big reasons often touted for assigning homework is that it builds time-management and resilience in children, but so does hard work in class.

I start every year by telling students that in our classroom I will make them a promise if they promise to work hard, then I promise to not assign homework beyond the 20 minutes of reading I expect every day outside of English. So seven years ago or so, I decided that I would try to limit the amount of homework as much possible, here is how we have done it. That some things that were not meant to take a long time did. That the kids who did the homework diligently didn’t really need to do it.

I realized that the kids who needed the extra practice, needed further teaching, not more work. I have written extensively about my decision to limit homework some of the many reasons include the research that tells us how little benefit homework has for kids, how much it drives stress, the research on how much teachers versus students speak, but most importantly my students telling me how they really feel about our homework practices. Well, it turns out that there is a way to do this, where I am able to ask students to read outside of class but almost nothing else. Yet, the other day, as I presented a workshop on passionate literacy, someone asked me how much homework my students have, when I told her they are asked to read 20 minutes and that is pretty much it, she was surprised.Īfter all, how can we cover everything there is to do when we only have 45 minutes without giving homework? How can I provide enough practice for my students without telling them to work on something at home? How can I make sure they are ready for 8th grade, for high school, for college, for real life if I don’t ask them to work on things outside of class? Not because it is not worth writing about, but because I do not really give it. I realize I have not written much about homework the last few years.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)